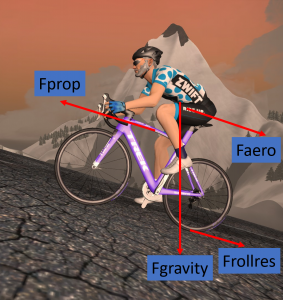

There are 4 forces that act on a cyclist and determine how fast the cyclist moves – propulsion, gravity, rolling resistance and aerodynamic drag. These four forces interact in various mixes with the conditions in which the cyclist is riding – wind, terrain, road surface, etc. In this blog I’ll discuss how a bike fit can impact these forces.

Propulsion (Fprop)

Propulsion is the force (torque) a cyclist exerts on the crank arm by contracting muscles. The torque causes the chain rings to rotate producing force on the chain then to the cogs and ultimately to the tire contacting the road. All of which moves the cyclist forward if the force overcomes the forces resisting movement forward.

The primary factors creating a cyclist’s propulsive force is his physical fitness – muscular strength, aerobic capacity, and economy – all of which are primarily determined by the cyclist’s training and somewhat by his genetics. A great training plan specific to the cyclist’s needs should produce a more powerful cyclist.

One area that bike fit can improve propulsive forces is in muscle range of motion. Muscles operate most powerfully and efficiently in the middle of their range of motion. At the end of muscle range of motion power is lost. For example, a saddle that is too high and causes the quads and hamstrings to operate at the end of their range of motion can rob the cyclist of power. An appropriate saddle height should yield a more powerful cyclist.

Gravity (Fgravity)

Gravity is the force pulling the cyclist down toward the earth. On a perfectly flat road there is minimal resistance to moving the bike forward due to gravitational forces. On a road with a 10% grade there is a substantial gravity force resisting the cyclist’s propulsive forces. In this case the cyclist’s weight determines the force due to gravity. A common measure for cycling performance is power to body weight ratio (w/kg). A lighter rider will find it easier to go up hill than the same rider but 10 pounds heavier. Want to be faster in the hills – lose weight or become stronger or both.

Rolling Resistance (Frollres)

Rolling resistance is the force due to mechanical friction in the drive train – bearings, chain, cogs, pulley wheels, etc. And from energy losses in the tire rubber. Coefficient of rolling resistance defines a tire’s resistance to rolling forward. There are websites devoted to measuring and documenting the rolling resistance of bike tires. The Frollres forces are small compared to aerodynamic drag. However, optimized components such as ceramic bearings, over-size pulley wheels and high-tech rubber compounds for tires all reduce rolling resistance.

Aerodynamic Drag (Faero)

Aerodynamic drag is the force that pulls the rider backward from behind. Aerodynamic drag is a complex force that is a function of the velocity of the bike, the velocity of the wind, the air density, the cyclist/bike aerodynamic drag coefficient and the frontal surface area of the cyclist and bike.

Aerodynamic drag is by far the largest force acting on the cyclist and bike. On a flat course aerodynamic drag accounts for about 90% of the speed loss due to the forces acting on the cyclist. At a 2% grade the losses due to aerodynamic drag and due to gravity are about equal. At an 8% grade gravity accounts for about 90% of the speed loss. Here the cyclist’s power to weight ratio determines the cyclist’s performance.

Bike Fit Goals

A time trial or triathlon bike and a great bike fit can make dramatic reductions in aerodynamic drag. The goal for a TT or triathlon bike is an aerodynamic position that minimizes drag, that is powerful and that is sustainable. The cyclist should be able to maintain the aero position for the duration of his event. And in the case of a triathlete run well off the bike. For a road bike cyclist, a great bike fit will enable him to achieve a better aerodynamic position in the handlebar drops and maximize power and comfort.